Fatigue is a complex and multifactorial experience that transcends mere physical tiredness, weaving itself into the emotional, cognitive, and metabolic realms of our daily lives. Among the myriad influences on our energy levels, dietary choices emerge as one of the most overlooked yet profoundly impactful contributors. Many individuals, in their search for vitality, overlook the subtle dietary culprits that stealthily deplete their energy reserves. This exploration of what foods make you fatigued is not only vital for those managing chronic tiredness but also essential for anyone aiming to optimize cognitive performance and emotional resilience. Understanding the direct and indirect ways in which food affects our energy metabolism can illuminate the path toward sustained vitality and mental clarity.

The paradox of modern nutrition lies in its abundance: the proliferation of processed convenience foods, sugar-laden snacks, and refined carbohydrates offers immediate gratification at the cost of long-term energy stability. These items may not always be recognized as the causes of fatigue, but their physiological consequences often tell a different story. From insulin spikes to gut dysbiosis and hormonal imbalances, the cumulative effect of poor dietary choices leads to an insidious drain on mental and physical stamina. As we peel back the layers of dietary fatigue triggers, we simultaneously unveil powerful solutions rooted in adaptogenic nutrition. Adaptogens, a class of natural substances revered for their ability to restore balance and resist stressors, present a promising counterbalance to the energy-depleting effects of modern diets.

You may also like: Unlock Powerful Stress-Relief with Adaptogenic Mushrooms and Stamina Herbal Support

The Physiology of Fatigue: Why Energy Falters Despite Adequate Rest

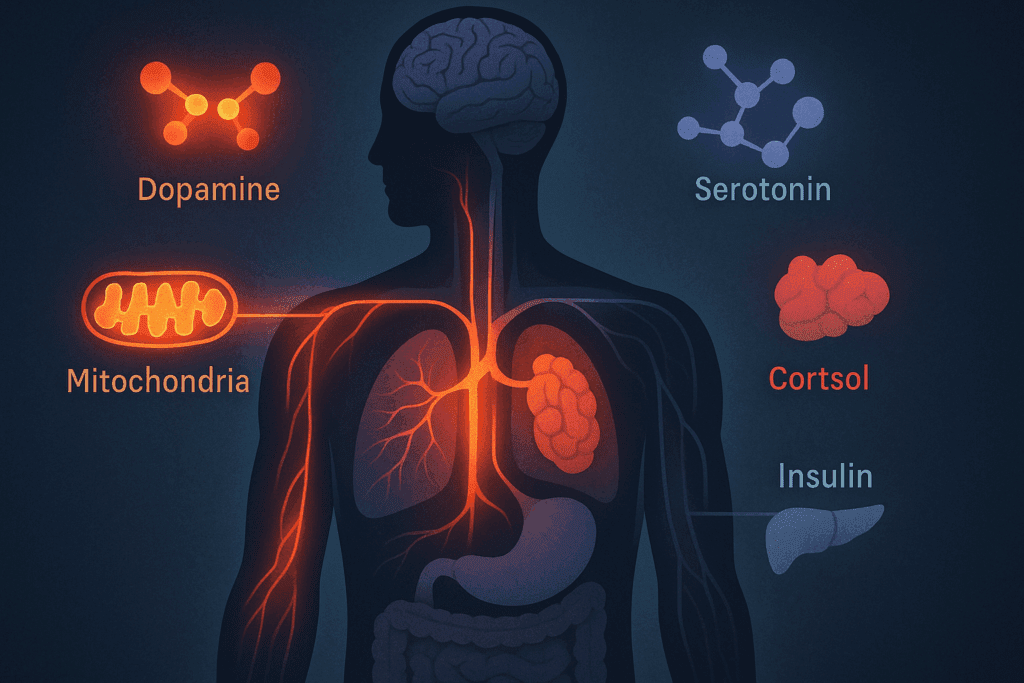

To understand how food influences fatigue, we must first examine how the body produces and regulates energy. At its core, fatigue arises from disruptions in cellular energy production, hormonal signaling, or neurotransmitter balance. Mitochondria, the cellular powerhouses, require a precise array of nutrients to function optimally. When deprived of essential cofactors such as magnesium, B vitamins, and amino acids, mitochondrial output declines, and fatigue ensues. However, it is not merely the absence of these nutrients that triggers fatigue—often, the presence of antagonistic compounds, such as excessive sugar or trans fats, impairs mitochondrial efficiency.

Hormonal regulation also plays a critical role in energy levels. Cortisol, the stress hormone, follows a diurnal pattern and helps mobilize energy reserves in response to perceived threats. Chronic dietary stress, in the form of high glycemic foods or stimulant overuse, can dysregulate cortisol rhythms, leading to morning lethargy and evening restlessness. Similarly, insulin resistance, often precipitated by poor dietary habits, disrupts glucose metabolism and starves cells of their primary fuel source. The result is a paradoxical state where blood sugar is high, but energy availability is low.

Neurotransmitter dynamics further complicate the fatigue landscape. Serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine all influence alertness, motivation, and mental clarity. Diets deficient in protein, omega-3 fatty acids, or antioxidants impair the synthesis and function of these brain chemicals, promoting mental fatigue and emotional instability. Thus, what appears as a simple lack of energy may in fact stem from a cascade of interconnected metabolic disruptions, many of which are diet-induced.

Processed Carbohydrates and the Energy Crash Cycle

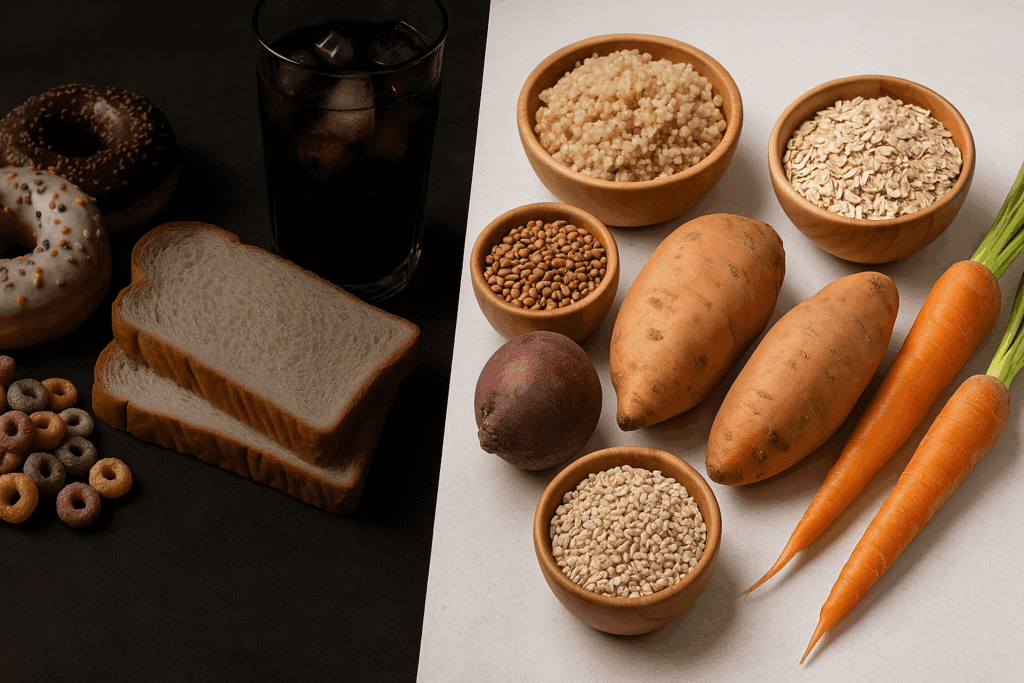

One of the most significant dietary contributors to fatigue is the overconsumption of processed carbohydrates. While these foods provide a quick source of glucose, they also set the stage for rapid blood sugar spikes followed by precipitous crashes. White bread, pastries, breakfast cereals, and sugary beverages flood the bloodstream with glucose, prompting a surge in insulin. This hormonal response swiftly reduces blood sugar, often overshooting its mark and resulting in hypoglycemia—a state characterized by shakiness, irritability, mental fog, and profound fatigue.

Frequent blood sugar fluctuations undermine metabolic stability and place stress on the adrenal glands, which must compensate with increased cortisol production. Over time, this pattern contributes to adrenal fatigue, a controversial but widely reported phenomenon marked by exhaustion, sleep disturbances, and stress intolerance. The repetitive nature of this energy rollercoaster also conditions the brain to crave more sugar for quick relief, perpetuating a vicious cycle of dependency and depletion. While such foods are marketed as energy boosters, they ironically become the very cause of persistent tiredness and reduced productivity.

Moreover, processed carbohydrates lack the fiber and micronutrients necessary for sustained energy production. In contrast, whole grains, legumes, and root vegetables offer complex carbohydrates that digest slowly and maintain stable glucose levels. Choosing nutrient-dense carbohydrates not only supports mitochondrial function but also fosters satiety and cognitive endurance. The key is not to eliminate carbohydrates entirely but to discern between those that nourish and those that exhaust.

Hidden Sources of Fatigue: What Foods Make You Fatigued Without You Realizing It

When considering what foods make you fatigued, it’s essential to look beyond the obvious culprits and examine the subtler dietary saboteurs. For instance, certain food additives, preservatives, and artificial sweeteners have been implicated in metabolic disruptions and neurological symptoms. Monosodium glutamate (MSG), commonly used in savory snacks and restaurant foods, can overstimulate glutamate receptors in the brain and provoke symptoms such as headaches, fatigue, and brain fog. Likewise, artificial sweeteners like aspartame and sucralose may interfere with gut microbiota and neurotransmitter balance, subtly eroding energy levels over time.

Dairy and gluten, while nourishing to some, are sources of fatigue in sensitive individuals. Food intolerances, often undiagnosed, provoke low-grade inflammation and immune activation, diverting metabolic resources away from energy production. The symptoms are rarely immediate, which makes the connection between certain foods and chronic tiredness difficult to detect. Fatigue after eating may be dismissed as normal postprandial drowsiness, yet it could be a signal of immunological stress triggered by specific dietary antigens.

Even ostensibly healthy foods can contribute to food exhaustion if they are consumed in an imbalanced context. Over-reliance on smoothies, salads, or low-calorie meals may deprive the body of adequate protein and fats, both of which are essential for satiety and energy stability. The modern wellness culture’s emphasis on “clean eating” sometimes inadvertently promotes energy deficiency by glorifying undernourishment. Recognizing the nuanced ways that seemingly benign foods impact our vitality requires both introspection and informed dietary experimentation.

Fatigue After Meals: Understanding the Connection Between Food and Tiredness

One of the most perplexing phenomena in nutrition science is the lack of energy after eating. For many, meals become a prelude to drowsiness rather than refreshment. While part of this can be attributed to natural postprandial processes, such as increased parasympathetic activity and digestion-related blood flow redistribution, excessive fatigue is not a normal consequence of eating. It often reflects imbalanced macronutrient composition, insulin dysregulation, or unrecognized food sensitivities.

Meals high in refined carbohydrates and low in fiber are especially notorious for inducing food and tiredness. A breakfast of pancakes and syrup, for example, may deliver an initial surge of glucose but quickly devolves into sluggishness as insulin clears the sugar from circulation. The absence of protein or fat exacerbates this effect by removing the braking mechanisms that slow gastric emptying and modulate glycemic response. Incorporating more balanced meals, rich in whole foods and adequate protein, can substantially reduce this post-meal dip.

Hydration also plays a pivotal role in postprandial fatigue. Dehydration impairs blood volume and oxygen delivery to tissues, reducing both physical and mental performance. In many cases, fatigue after eating is not solely about what is consumed, but also what is lacking—namely, water, electrolytes, and restorative micronutrients. Addressing the root causes of post-meal fatigue involves a holistic assessment of dietary patterns, digestion, and individual metabolic responses.

Gut Health, Inflammation, and the Fatigue Link

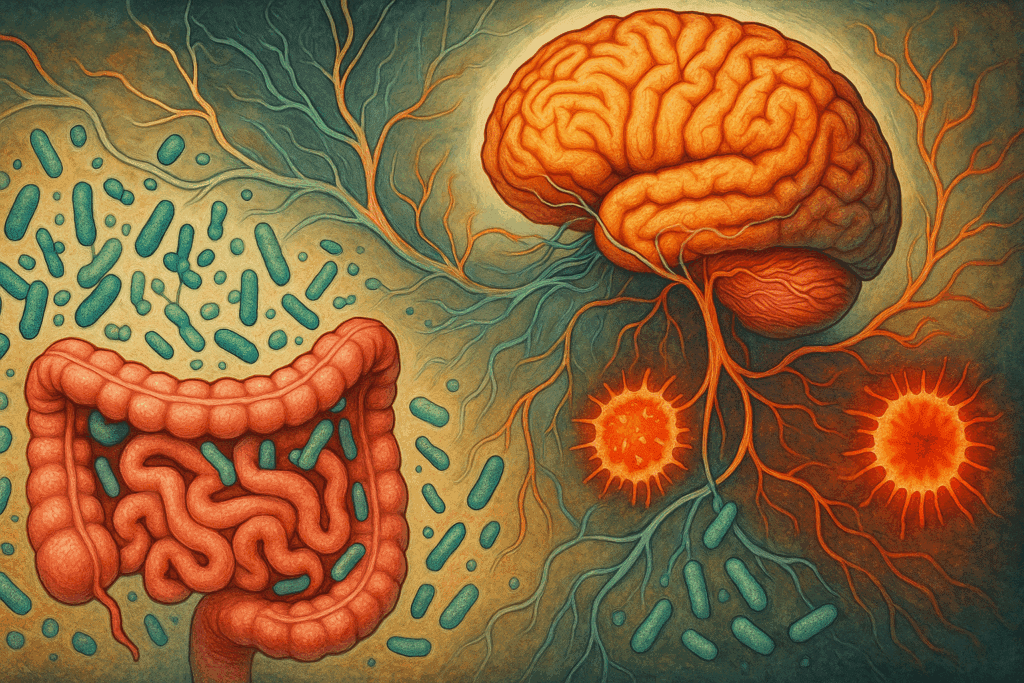

The gut-brain axis represents one of the most dynamic and influential systems affecting energy levels. Imbalances in gut microbiota, often caused by diets high in sugar, alcohol, or antibiotics, lead to increased intestinal permeability—commonly known as “leaky gut.”—This condition allows inflammatory compounds to enter the bloodstream, where they can affect mitochondrial function and brain chemistry. Inflammatory cytokines have been shown to reduce dopamine levels and interfere with hypothalamic regulation, resulting in feelings of fatigue, anhedonia, and poor concentration.

Diet-induced dysbiosis is one of the hidden triggers of food exhaustion, particularly when coupled with chronic stress. The overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria and yeasts consumes nutrients and generates metabolic byproducts that further tax the liver and immune system. This sets the stage for a systemic energy deficit that no amount of sleep can rectify. Rebalancing the gut through prebiotic and probiotic-rich foods, along with anti-inflammatory dietary choices, offers a powerful route to restoring energy resilience.

Fermented foods such as kimchi, kefir, and miso not only replenish beneficial bacteria but also enhance nutrient absorption and neurotransmitter production. Their inclusion in a strategic nutritional plan can mitigate the inflammatory fatigue cascade and support both gastrointestinal and neurological vitality. Paying attention to the interplay between food, gut health, and energy is essential in crafting a fatigue-resistant lifestyle.

What Foods Make You Fatigued When You’re Under Stress?

Stress and fatigue are deeply entwined, and diet serves as both a trigger and a remedy. During periods of heightened stress, the body prioritizes survival mechanisms, often at the expense of digestion, detoxification, and repair. High-stress eating patterns typically include caffeine, sugar, alcohol, and convenience foods—each of which exacerbates hormonal imbalances and contributes to fatigue. Understanding what foods make you fatigued under stress reveals not only nutritional pitfalls but also behavioral patterns rooted in emotional coping.

Caffeine, though temporarily energizing, creates a false sense of alertness that masks underlying exhaustion. As tolerance builds, larger doses are required to achieve the same effect, leading to adrenal dysregulation and sleep disturbances. Similarly, alcohol disrupts sleep architecture, impairs nutrient absorption, and taxes the liver—resulting in a compounded sense of fatigue, especially the morning after. Stress eating often involves processed snacks and high-sugar items that offer fleeting comfort but leave behind biochemical chaos.

In contrast, stress-resilient nutrition emphasizes magnesium-rich greens, complex carbohydrates, healthy fats, and adaptogenic herbs. These choices stabilize blood sugar, support adrenal function, and enhance neurotransmitter synthesis. Replacing reactive eating habits with intentional, nutrient-dense meals is a transformative step toward breaking the fatigue-stress loop. When the body receives the biochemical support it needs, it can better withstand emotional turmoil and maintain consistent energy output.

Adaptogens and Their Role in Counteracting Food-Induced Fatigue

Adaptogens are nature’s answer to the stress-fatigue dilemma. These botanicals help the body modulate stress responses, improve hormonal balance, and enhance mitochondrial function—making them invaluable allies in the quest for sustained energy. Ashwagandha, Rhodiola rosea, and Eleuthero are among the most researched adaptogens for fatigue relief. By regulating cortisol, enhancing resilience to stress, and promoting restorative sleep, they address many of the downstream effects of dietary fatigue triggers.

Ashwagandha, for example, has been shown to reduce cortisol levels, support thyroid function, and improve stamina. Rhodiola rosea enhances mental clarity and reduces perceived exertion during physical activity, while Eleuthero boosts endurance and immune response. These herbs do not stimulate energy in the way caffeine does; rather, they fortify the body’s adaptive capacity, allowing it to produce energy more efficiently and recover from stress more quickly.

Adaptogens also influence neurotransmitter activity, particularly in the realms of serotonin and dopamine, which are critical to motivation and focus. By improving receptor sensitivity and reducing neuroinflammation, adaptogens help restore the mental energy often depleted by poor diet or chronic stress. Their versatility and safety profile make them an ideal adjunct to dietary interventions aimed at reducing food-related fatigue.

What Foods Make You Fatigued and How to Replace Them Mindfully

Once we identify what foods make you fatigued, the next logical step is to replace them with energizing alternatives that nourish rather than deplete. Swapping sugary cereals for steel-cut oats with seeds and berries offers complex carbohydrates, fiber, and antioxidants that support metabolic health. Replacing soda with herbal teas or infused water reduces sugar intake while enhancing hydration and detoxification.

Mindful eating also means paying attention to food timing and portion sizes. Large, heavy meals can overload digestion and sap energy, particularly when consumed late in the evening. Smaller, balanced meals eaten at regular intervals help maintain stable blood sugar and support sustained energy. Listening to hunger cues and avoiding emotional eating patterns further refines energy balance.

Incorporating energy-boosting superfoods such as spirulina, maca root, chia seeds, and medicinal mushrooms adds a functional dimension to daily nutrition. These foods provide a rich matrix of vitamins, minerals, and adaptogenic compounds that enhance mitochondrial performance and reduce oxidative stress. The art of energy nutrition lies not only in what is removed but also in what is added to support the body’s dynamic needs.

Beyond Diet: Lifestyle Strategies for Reducing Food Exhaustion

While nutrition forms the foundation of energy resilience, lifestyle factors play a synergistic role. Sleep hygiene, physical activity, sunlight exposure, and stress management practices amplify the benefits of a fatigue-conscious diet. Chronically poor sleep, for instance, reduces insulin sensitivity and disrupts circadian rhythms, making it harder to regulate appetite and energy. Regular physical movement improves mitochondrial density and glucose utilization, directly countering the effects of food-induced lethargy.

Mindfulness practices such as yoga, meditation, and breathwork reduce sympathetic nervous system overactivity and enhance vagal tone, supporting digestive and hormonal balance. Exposure to natural light, especially in the morning, resets circadian rhythms and promotes melatonin production at night, improving sleep quality and next-day alertness. Each of these lifestyle elements serves as a multiplier for the dietary strategies discussed earlier, creating a holistic framework for energy optimization.

Environmental toxins, often overlooked, also play a role in energy depletion. Heavy metals, mold, and chemical additives burden the liver and interfere with mitochondrial function. Detoxification-supportive practices, such as sweating, dry brushing, and adequate fiber intake, help reduce toxic load and restore energy capacity. Viewing fatigue through a systems lens reveals that every input—nutritional, emotional, environmental—interacts to shape our energetic landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): Uncovering Fatigue, Food, and Adaptogens

What Foods Make You Fatigued Even If You Eat “Healthy”?

Surprisingly, even foods labeled as “healthy” can contribute to fatigue if consumed without attention to balance or individual tolerance. For instance, relying heavily on low-fat salads without sufficient protein or healthy fats can cause blood sugar fluctuations that lead to food exhaustion and a noticeable dip in energy. Additionally, foods like gluten-free snacks or vegan alternatives often contain hidden sugars or processed starches that trigger the same metabolic crashes associated with junk food. People also underestimate the fatigue-inducing potential of repetitive meals; eating the same nutrient-limited foods can lead to micronutrient deficiencies over time. Even healthy eaters should vary their diet and monitor how specific combinations affect their energy levels throughout the day to minimize lack of energy after eating.

Why Do I Feel More Tired After Meals That Include Gluten or Dairy?

The relationship between food and tiredness becomes clearer when examining immune responses to gluten and dairy. For individuals with sensitivities—whether diagnosed or not—consumption of these proteins can trigger systemic inflammation, which diverts metabolic resources away from energy production. This immune activation can also increase intestinal permeability and disrupt gut microbiota, leading to a cascade of fatigue-related symptoms such as brain fog, sluggish digestion, and muscle weakness. Beyond physiological effects, emotional and cognitive fatigue can also result from the neurotransmitter imbalances caused by chronic inflammation. If you consistently notice food exhaustion after consuming gluten or dairy, a temporary elimination diet guided by a nutrition professional may be worth exploring.

Can What Foods Make You Fatigued Differ Depending on Your Circadian Rhythm?

Absolutely, circadian biology plays a key role in how food impacts energy. Consuming high-carbohydrate meals late in the evening can impair sleep quality and contribute to morning lethargy due to altered melatonin and insulin signaling. Night owls who eat large dinners close to bedtime often experience food and tiredness the following morning, even if their total caloric intake is reasonable. Meanwhile, early birds may find that skipping breakfast leads to food exhaustion later in the day, especially if their body is accustomed to using morning meals to kick-start metabolism. Personalized eating schedules aligned with circadian rhythms can help reduce the risk of post-meal drowsiness and improve sustained energy. Emerging research in chrono-nutrition supports the idea that not only what we eat—but also when we eat—affects how food either energizes or fatigues us.

How Do Ultra-Processed Foods Disrupt Energy Beyond Sugar Crashes?

Ultra-processed foods contain more than just refined sugars; they often harbor emulsifiers, colorants, preservatives, and flavor enhancers that interfere with hormonal and metabolic balance. These compounds can impair mitochondrial function and increase oxidative stress, both of which are deeply associated with chronic fatigue. For example, common preservatives like sodium benzoate have been linked to mitochondrial damage and may contribute to food exhaustion even in small doses over time. Furthermore, the lack of natural enzymes and fiber in ultra-processed foods burdens the digestive system, making it harder for the body to extract and utilize nutrients efficiently. The cumulative effect is not just a sugar crash, but a lingering state of fatigue that persists regardless of how much rest one gets.

What Are Some Unexpected Signs of Food Exhaustion?

Fatigue triggered by food doesn’t always manifest as outright tiredness—it can show up subtly through decreased motivation, irritability, delayed reaction time, or even procrastination. You might also notice that routine tasks feel disproportionately difficult or that you require caffeine to recover from meals. Another overlooked symptom is disrupted sleep cycles, where fatigue after eating eventually snowballs into nighttime restlessness or early morning awakenings. Recurrent cravings, especially for sugar or carbohydrates, may be a biochemical signal of fluctuating blood glucose tied to the foods that cause drowsiness. These secondary symptoms are crucial for identifying the deeper causes of food-related fatigue, especially when traditional signs like yawning or sleepiness are not present.

How Can You Tell If Your Post-Meal Fatigue Is From a Food Intolerance?

If your fatigue consistently follows consumption of certain meals but doesn’t always align with portion size or calorie content, food intolerance could be at play. Keeping a detailed food and symptom journal for 2–3 weeks can reveal patterns linking specific ingredients with energy slumps. Unlike food allergies, which trigger rapid immune responses, intolerances lead to slower and often cumulative symptoms—making them harder to detect. Signs that fatigue is driven by intolerance include persistent bloating, mood changes, headaches, or joint stiffness within hours of eating. Eliminating and then reintroducing suspected triggers under professional supervision is a validated method to determine if food and tiredness are linked to intolerances.

Are There Psychological or Behavioral Factors That Worsen Food-Related Fatigue?

Yes, psychological patterns such as emotional eating, reward-driven food choices, and stress-induced cravings can exacerbate fatigue. Many individuals use food as a coping mechanism, reaching for high-sugar or high-fat comfort foods during periods of emotional stress, which then result in blood sugar imbalances and increased fatigue. Behavioral habits like eating quickly, skipping meals, or multitasking during meals can impair digestion and reduce nutrient absorption—contributing to lack of energy after eating. Cognitive fatigue, driven by decision overload or anxiety, can also push individuals toward energy-draining snacks instead of nutrient-dense options. Cultivating mindfulness during meals, and addressing underlying emotional triggers, can play a significant role in breaking the cycle of food exhaustion.

What Foods Make You Fatigued Most Often During Travel or Jet Lag?

During travel—especially across time zones—people often rely on airport snacks, hotel buffets, and packaged meals that are high in sodium, sugar, and preservatives. These foods not only destabilize blood sugar but also aggravate dehydration and digestive sluggishness, all of which contribute to significant fatigue. When circadian rhythms are disrupted, the body becomes more sensitive to what foods can make you sleepy, especially starchy, processed meals eaten at odd hours. Reduced sunlight exposure and poor sleep compound the effects of food-related tiredness, making recovery even slower. Travelers can counteract these issues by hydrating consistently, choosing whole-food options like nuts, fruit, or hard-boiled eggs, and aligning their meal schedule with the local daylight cycle as soon as possible.

How Do Adaptogens Address the Root Causes of Food-Related Fatigue?

Unlike stimulants that mask fatigue symptoms, adaptogens work at the hormonal and cellular level to help the body recover its baseline energy rhythm. They modulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates cortisol and other stress hormones that influence energy production. For example, holy basil and reishi mushroom have been shown to reduce post-meal fatigue by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing inflammation, both of which are common in people who frequently experience lack of energy after eating. Adaptogens also support mitochondrial health, enhancing ATP production—the body’s primary energy currency. Over time, this results in improved metabolic flexibility and reduced dependency on quick-fix energy sources like caffeine or sugar.

What Foods Make You Fatigued When Combined Improperly in a Single Meal?

Meal composition matters as much as individual ingredients. Combining fast-digesting carbohydrates (like white rice or white bread) with little to no protein or fat can lead to rapid glucose spikes followed by sharp crashes in energy. Additionally, pairing high-fat meals with sugar-laden desserts slows gastric emptying and impairs insulin sensitivity, increasing the likelihood of post-meal food and tiredness. Even natural sugars—like those in fruit juices—can become problematic when consumed with starchy meals, enhancing the glycemic load and exacerbating food exhaustion. Thoughtful meal planning that balances macronutrients and includes fiber can mitigate these issues, creating meals that stabilize rather than sabotage energy levels. As a practical guideline, strive for meals that contain a source of clean protein, complex carbs, and healthy fats to support sustained energy and reduce the risk of drowsiness.

Conclusion: Restoring Vitality by Rethinking What Foods Make You Fatigued

In a world increasingly shaped by convenience, reclaiming our energy requires a deliberate and informed approach to diet and lifestyle. By identifying what foods make you fatigued and understanding the biochemical mechanisms behind their effects, we gain the power to reshape our habits and restore vitality. The fatigue epidemic is not merely a function of modern stress but also a reflection of widespread nutritional neglect and disconnection from the rhythms of nature.

Integrating adaptogenic herbs, mindful eating practices, and gut-nourishing foods creates a resilient foundation for both physical and mental stamina. As we replace energy-depleting foods with nutrient-dense alternatives and incorporate lifestyle practices that support cellular function, we move closer to sustainable well-being. This journey demands awareness, experimentation, and commitment, but the reward is profound: a life marked not by chronic fatigue, but by clarity, endurance, and joy.

The path forward is not about restriction but restoration. It is about listening to the body’s wisdom, honoring its needs, and choosing foods that energize rather than exhaust. In doing so, we align with the deeper rhythms of health and unlock our innate potential for vibrant living.

Further Reading:

Tired After Eating? Here’s Why